American

Bittern

Botaurus lentiginosus

American

Bittern

Botaurus lentiginosus

A secretive bird of marshes, the American Bittern has long been considered primarily a winter visitor to San Diego County. In this role it is now rare and decreasing. In the breeding season the American Bittern is also rare, with the first suggestion of actual nesting only in 1983. Yet from 1997 to 2001 we found possibly breeding bitterns at eight sites, almost as many as where we found the species wintering—an unexpected twist. A family at the mouth of Las Flores Creek in 1998 provided us with the first evidence of successful fledging of American Bitterns in San Diego County, the southern tip of the species’ breeding range along the Pacific coast.

Breeding distribution: In the marsh at the mouth of Las Flores Creek (E3), American Bitterns were regular in 1998 and 1999, with two calling males 15 May 1999 and one calling male, an apparent adult female, and a fledgling 6 June 1998 (R. and S. L. Breisch). The other sites where the species possibly bred during the atlas period were Guajome Lake (G7; up to five on 8 May 2001, C. Andregg), Buena Vista Lagoon (one west of Interstate 5, H5, 18 July 1998, K. Messer, and 29 May 2001, R. Gransbury; two east of the freeway, H6, 11 August 1998, J. Ginger), the mouth of Agua Hedionda Creek (I6; one on 22 April 1998, W. E. Haas), San Elijo Lagoon (L7; four records of single birds, one as late as 1 June 1998, A. Mauro), lower Los Peñasquitos Canyon (N8; one on 7 May 2000, P. A. Ginsburg), and the Dairy Mart pond, Tijuana River valley (V11; up to two on 28 May 2001, G. McCaskie). The species had summered at least irregularly at Guajome Lake, San Elijo Lagoon, and the Tijuana River valley since the 1980s.

One at O’Neill Lake (E6) 19 April 1999 was in suitable habitat but not relocated in spite of thorough coverage so was most likely a late migrant (P. A. Ginsburg). Unexpected were two American Bitterns away from extensive marshes in midsummer: one in Woods Valley (H12) 19 June 1998 (W. E. Haas) and one along the San Diego River near Boulder Creek (L17) 28 June 1997 (R. C. Sanger).

Nesting: American Bittern nests are usually built over water within dense marshes, making them difficult to find. The only nesting confirmation in San Diego County before that at Las Flores Creek was a sighting of one carrying nest material at Border Field State Park (W10) 26 June 1983 (J. Oldenettel).

Migration: At O’Neill Lake, which P. A. Ginsburg covered intensively year round, he found the American Bittern in the spring as late as 19 April (1999) and in fall as early as 27 August (1997 and 1998). Outside the coastal lowland, records of spring migrants are of one at Jacumba (U28) 10 April 1976 (G. McCaskie), two at Lake Domingo (U26) 17 April 1998 (F. L. Unmack), one at Lower Willows, Coyote Creek (D23), 25 April 1981 (A. G. Morley), and one in the unsuitable habitat of Tamarisk Grove Campground (I24) 25 April 1982 (D. K. Adams). Records of fall migrants are of one found dead along Henderson Canyon Road, Borrego Valley (E24) 29 September 2002 (P. D. Jorgensen, SDNHM 50681) and one at Little Pass, between Earthquake and Blair valleys (K24) 3 October 1975 (ABDSP database).

Winter: During the atlas period we noted the American Bittern in winter 22 times at 11 sites, all but one in the coastal lowland and most in the valleys of the lower Santa Margarita and San Luis Rey rivers. Our only sightings of more than a single individual were of two at O’Neill Lake 13 December 1999 (P. A. Ginsburg) and two in the Tijuana River estuary (V10) 24 January 1998 (B. C. Moore). The salt marsh in the Tijuana estuary was our only winter site for the species that was not freshwater marsh.

The American Bittern has been noted twice on Lake Henshaw Christmas bird counts, apparently the only winter records for the species at higher elevations in San Diego County: one at Lake Henshaw (G17) 19 December 1983 (D. K. Adams et al.) and one in Matagual Valley (H19) 18 December 2000 (G. Morse).

Conservation: Both atlas results and Christmas bird counts reveal a downward trend in the number of American Bitterns wintering in San Diego County. In the 1970s, counts at the Santa Margarita River mouth, Batiquitos Lagoon, and San Elijo Lagoon ranged up to four or five per day (Unitt 1984, King et al. 1987), but these numbers could not be equaled from 1997 to 2002 despite greater effort. The annual average on San Diego Christmas bird counts from 1975 to 1984 was 1.6 but dropped to 0.7 from 1992 to 2001. On the Oceanside count, the annual average over the same periods dropped from 3.1 to 0.9. Presumably the change in San Diego County reflects the decline across the species’ range, due to the elimination and degradation of wetlands (Gibbs et al. 1992). Stephens (1919a) called the American Bittern “rather common”; Sams and Stott (1959) wrote that it was easily found at Mission Bay before most of the marsh there was destroyed in the 1950s.

Least

Bittern

Ixobrychus exilis

Least

Bittern

Ixobrychus exilis

An uncommon to rare and localized resident of marshes of cattail and tule, the Least Bittern is one of the more difficult species for the San Diego County birder to see. It is somewhat more numerous—or maybe just more conspicuous—in summer. Nevertheless, atlas observers found it to be regular in winter, a status it did not have—or was unknown—25 years earlier. Another perspective on the Least Bittern in San Diego County comes from wildlife rehabilitators. Each year, in late summer and fall, they receive several dispersing juvenile Least Bitterns that met a mishap in urban areas unsuitable for them.

Breeding distribution: Habitat for the Least Bittern lies largely in the coastal lowland, at brackish lagoons and lakes, ponds, and streams inland. Our most frequent sites for the species during the atlas period were O’Neill Lake, Camp Pendleton (E6; up to four on 21 and 29 July 1998, P. A. Ginsburg), the San Diego River between Santee and Lakeside (P13; up to three on 26 April 1997, D. C. Seals), and Lake Murray (Q11; up to three on 22 August 1998, S. R. Helm). All sites where we recorded the species in spring and summer represent likely breeding sites, but the only locations where we actually confirmed breeding 1997–2001 were O’Neill Lake (fledgling 21 July 1998, P. A. Ginsburg), the east basin of Buena Vista Lagoon (H6; adult feeding young 18 July 1999, L. E. Taylor), Discovery Lake, San Marcos (J9; fledgling 17 May 1998, J. O. Zimmer), the borrow pit in the Sweetwater River at Dehesa (Q15; fledging 14 June 2001, H. L. Young), and the San Diego River in Mission Valley near Mission Center Road (R9; four fledglings with adult 3 May 1997, J. K. Wilson). Least Bitterns are known to nest also at San Elijo Lagoon (King et al. 1987). It is likely that only the species’ secretive habits accounted for our missing it at some sites where it had been seen repeatedly before the atlas period, especially Guajome Lake (G7) and the upper end of Batiquitos Lagoon (J7).

The Least Bittern also occurs rarely on the Campo Plateau. Sams and Stott (1959) reported it at Campo Lake (U22). We found it twice at Lake Domingo (U26; one on 24 June 1999 and 21 April 2000) and three times at Tule Lake (T27), the best habitat for it in this region (one on 20 April and 3 July 2000; two, including an independent juvenile, 6 June 2001, J. K. Wilson, F. L. Unmack).

Nesting: The Least Bittern hides its nest effectively, screening it with a canopy of surrounding vegetation as well as building within the marsh itself. It is no surprise that atlas observers found no nests. Dates of eight egg sets collected 1901–37 range from 20 May to 8 July, but our earliest date of fledglings during the atlas period, 3 May, implies egg laying as early as about 1 April. A family of three fledglings with adults along the San Diego River in Mission Valley 16 August 1990 must have hatched from eggs laid in early July (P. Unitt).

Migration: With the increase in winter records of the Least Bittern, the species no longer follows a clearly defined seasonal schedule. Nevertheless, juveniles found away from marshes in developed areas demonstrate at least short-distance dispersal. Their dates range from 25 June (1991, near Chollas Reservoir, R11, SDNHM 47680) to 30 September (1998, Paradise Hills, T11, SDNHM 50223).

Winter: We noted the Least Bittern in winter on 44 occasions at about 16 sites from 1997 to 2002. Our largest winter numbers were five at O’Neill Lake 4 December 1999 (P. A. Ginsburg), four at Windmill Lake (G6) 26 December 1998 (P. Unitt), and four at Miramar Lake (N10) 29 January 1998 (M. B. Stowe). Most of the winter records are from sites where the species was regular during the breeding season. All are in the coastal lowland, and most are in northwestern San Diego County where freshwater marshes are more frequent.

Conservation: Numbers of the Least Bittern are generally thought to have declined in parallel with the elimination of freshwater marshes. The species is so difficult to monitor, however, that real evidence for a decline is lacking at least in San Diego County. Its history in Mission Valley shows it retains the ability to recolonize regenerated habitat. In 1988, all vegetation along the San Diego River between Highway 163 and Stadium Way was removed, and the river banks were recontoured, as part of the “First San Diego River Improvement Project.” The bitterns recolonized and nested successfully in 1990, the first year in which stands of cattails had regrown to full size.

Before 1981, there were only eight San Diego County records for December and January (Unitt 1984). It is unclear whether the apparent increase in winter is real or whether it is an artifact of birders’ covering the wintering sites more consistently and being more aware of the species’ calls.

Taxonomy: All Least Bitterns in North America are nominate I. e. exilis (Gmelin, 1789); the supposed western subspecies I. e. hesperis Dickey and van Rossem, 1924, is invalid (Dickerman 1973).

Great

Blue Heron

Ardea herodias

Great

Blue Heron

Ardea herodias

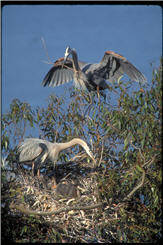

The Great Blue Heron is one of San Diego County’s most familiar water birds, occurring year round at wetlands of all kinds. It uses dry land, too, commonly foraging away from water for gophers and rats. Some Great Blue Herons nest as isolated pairs, but most are colonial, nesting high in tall trees. A majority of the county’s approximately 250–300 nesting pairs are concentrated in the six largest colonies. The Great Blue Heron has taken readily to artificial nesting habitat like eucalyptus groves; it feeds largely on prey introduced by man. Yet, unlike those of the Great and Snowy Egrets, the population of the Great Blue Heron has not exploded.

Breeding distribution: The Great Blue Heron nested at 30 recorded sites in San Diego County from 1997 to 2001. Thirteen of these had only isolated pairs, but 17 had from two to 54 nests (Table 6). Most of the colonies are in the coastal lowland, but a few are at higher elevations. The highest is at 4650 feet elevation in Rattlesnake Valley (N22) in the Laguna Mountains.

Table 6 Nesting Colonies of the Great Blue Heron in San Diego County, 1997–2001

|

Colony |

Square |

Maximum Count of Active Nests |

Year of Maximum |

Observer |

| O’Neill Lake |

E6 |

25 |

2000 |

P. A. Ginsburg |

| West Fork Conservation Camp |

E17 |

6+ |

2001 |

E. C. Hall, C. R. Mahrdt, J. O. Zimmer |

| Lake Henshaw |

G17 |

4 |

1998 |

P. Unitt |

| Highland Dr. at Oak Ave., Carlsbad |

I6 |

14 |

1999 |

P. A. Ginsburg |

| Batiquitos Lagoon |

J7 |

3 |

2000 |

J. Ciarletta |

| Wild Animal Park |

J12 |

“large” |

1997 |

D. C. Seals |

| Escondido Creek at La Bajada, Rancho Santa Fe |

L8 |

30 |

2000 |

A. Mauro |

| San Dieguito River mouth |

M7 |

2 |

2001 |

D. R. Grine |

| Lucky 5 Ranch, Rattlesnake Valley |

N22 |

2 |

1998, 99 |

P. D. Jorgensen |

| El Capitan Reservoir |

O16 |

1a |

1999, 2001 |

S. Kingswood |

| Lindo Lake |

P14 |

5 |

2001 |

C. G. Edwards |

| Sea World |

R8 |

52 |

1997 |

Black et al. (1997) |

| Point Loma |

S7 |

54 |

1999 |

M. F. Platter-Rieger |

| North Island Naval Air Station |

S8 |

22 |

1999 |

P. McDonald |

| Spreckels Park, Coronado |

S9 |

13 |

1998 |

Y. Ikegaya |

| Glorietta Blvd. at Miguel Ave., Coronado |

S9 |

9 |

1997 |

P. Unitt |

| Hitachi crane, National City |

T10 |

8b |

2000 |

R. T. Patton |

aOne nest of the Great Blue with more of the Great and Snowy Egrets.

bEight individuals; number of nests not specified.

Also, two or three pairs have built nests but apparently not fledged any young at Santee Lakes (P12), as in 2002 (M. B. Mulrooney).

Breeding Great Blue Herons apparently forage within 5 miles or so of their colonies; for example, the birds nesting at the Rancho Santa Fe colony appear to forage primarily at San Elijo Lagoon. Away from known or probable nest sites, the Great Blue Heron occurs widely but uncommonly through the breeding season, with up to five at, for example, Cuyamaca Lake (M20) 25 June 1998 (A. P. and T. E. Keenan), Barrett Lake (S18) 18 June 2000 (R. and S. L. Breisch), and Lake Morena (S21) 7 July 2001 (R. and S. L. Breisch).

Nesting: In San Diego County, most Great Blue Herons build stick nests in trees, often adding to them year after year. At O’Neill Lake, Batiquitos Lagoon, Rancho Santa Fe, and Lindo Lake they nest in eucalyptus trees, whereas at Carlsbad, Mission Bay, and Coronado they nest in planted pines. At North Island and Point Loma they nest in both. At the San Dieguito River mouth, Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7), and Sea World the herons nest in native or planted Torrey Pines, and at Pine Valley (P21) and Rattlesnake Valley they nest in tall Jeffrey pines. An isolated nest at the mouth of Couser Canyon (E10) was in a palm. In 1998 the colony at Lake Henshaw was in cottonwoods. Occasionally the herons use artificial structures; those reported during the atlas period were around San Diego Bay, on a crane in National City and on the catwalk of a power plant in Chula Vista. At least in 1994 the herons built 13 nests on abandoned platforms and barges off National City (T10; Manning 1995); we did not survey this site 1997–2001. Past nest sites included sycamores and a scrub oak among sandstone cliffs (WFVZ).

The Great Blue Heron’s exact nesting schedule is difficult to follow because its nests are in the treetops where their contents are not obvious until the chicks are well grown. The herons begin defending nest sites at the end of November (Black et al. 1997) and building or refurbishing their nests in early to mid January. They begin laying in early to mid January as well, as implied by hatching in mid February and fledglings by 4 April 1997 at Sea World (Black et al. 1997). Late February through March appears to be the time of peak laying. Herons nesting in established colonies may nest earlier than those in new colonies or those in isolated pairs. A nest at a new colony overlooking the San Dieguito River estuary still had young, nearly full grown, on 11 August 2001 (P. Unitt), suggesting laying as late as early June. At Point Loma some nests still had large young in mid September. Several Point Loma nests hatched and fledged two successive broods within the same year; it is unknown if the second brood was raised by the same parents (M. F. Platter-Rieger).

Migration: The Great Blue Heron is nonmigratory in southern California, but juveniles sometimes disperse long distances; an extreme example is of one tagged as a nestling in Orange County found the following winter at Elko, Nevada (K. Keane and P. H. Bloom). Surveys around San Diego Bay reveal somewhat higher numbers in fall, probably corresponding with the dispersal of juveniles (Macdonald et al. 1990, Stadtlander and Konecny 1994). Surveys at San Elijo Lagoon found somewhat lower numbers in spring, probably corresponding with adults spending more time at nesting colonies (King et al. 1987).

In the Anza–Borrego Desert, where it is a rare nonbreeding visitor, the Great Blue Heron occurs mainly in fall and winter; the only records from late April through June are of one at Scissors Crossing (J22) 14 May 1998 (E. C. Hall), one at Borrego Springs (G24) 14 May 2000 (P. D. Ache), one in the north Borrego Valley (E24) 8–11 June 2001 (P. D. Jorgensen), and one along Coyote Creek (D24) 26 June 1988 (A. G. Morley).

Winter: Atlas results suggest that the number of Great Blue Herons in San Diego County does not vary much with the seasons. Our highest winter counts in single atlas squares 1997–2002 were of 27 around north San Diego Bay 18 December 1999 (D. W. Povey, M. B. Mulrooney), 27 at the Wild Animal Park 3 January 1998 (K. L. Weaver), and 30 at Lake Henshaw 3 December 2000 (L. J. Hargrove). Thus many birds remain near the nesting colonies through the winter. Great Blue Herons range in winter as high as 4500–4600 feet elevation, in Lower Doane Valley (D14; one 31 December 1999–7 January 2000, P. D. Jorgensen), at Cuyamaca Lake (many observations, with up to five on 17 January 2000, G. Chaniot), and in Thing Valley (Q24; three records, J. R. Barth, P. Unitt). Wintering Great Blue Herons are irregular in the Borrego Valley, with five individuals seen during the atlas period and records on five of 18 Anza–Borrego Christmas bird counts 1984–2001, maximum three on 30 December 1990.

Conservation: In San Diego County the Great Blue Heron has become thoroughly integrated into the domesticated environment. Many colonies are directly over places heavily trafficked by people, the nesting birds being indifferent to human activity below. A study of the food of nestlings at the Point Loma colony in 1995 revealed the birds were fed largely on northern anchovy, crawfish, rats, domestic goldfish, and bullfrogs—hardly any of their diet consisted of items available before the founding of San Diego in 1769.

In spite of being something of an urban adapter, and establishing colonies at sites unsuitable before trees were planted there, the Great Blue Heron has increased in numbers only modestly. On the San Diego Christmas bird count, from 1953 to 1972, it averaged 61 (0.35 per party-hour); from 1997 to 2002, it averaged 113 (0.51 per party-hour). A factor likely keeping the population in check in San Diego County is the high rate of steatitis, an often fatal disease in which the birds are afflicted with large deposits of necrotic fat. Its cause is unknown, and its rate among other herons is much lower.

Taxonomy: The Great Blue Heron has been oversplit into many subspecies, primarily by Oberholser (1912). With most of these synonymized, the birds of southern California are best called A. h. wardi Ridgway, 1882 (Hancock and Kushlan 1984, R. W. Dickerman pers. comm.).

Great

Egret

Ardea alba

Great

Egret

Ardea alba

Decimated in southern California at the beginning of the 20th century, the Great Egret has enjoyed a recovery that is still continuing. In San Diego County it was long a nonbreeding visitor only, mainly in fall and winter, and it is still most numerous in that role. The first known nesting was in 1988, and more colonies formed soon thereafter, until by the arrival of the 21st century the county’s breeding population numbered about 75 pairs, most at the Wild Animal Park and Rancho Santa Fe. But the establishment of new colonies, often mixed with those of other herons, continued past the end of the atlas period in 2002.

Breeding distribution: The primary Great Egret colony in San Diego County, founded in 1989, is in the Wild Animal Park (J12), in the multispecies colony of herons and egrets in the Heart of Africa exhibit. Counts here range up to 100 birds on 15 June 1998 (D. and D. Bylin) and 40 nests on 9 May 1999 (K. L. Weaver). The colony in Rancho Santa Fe (L8), in eucalyptus trees within a private estate along Escondido Creek near La Bajada, is second in size. In 1998, the first year in which it nested there in numbers, there were 25 to 30 nests, with a similar number of Great Blue Heron nests (A. Mauro).

The other colonies established themselves after the atlas period began in 1997. At El Capitan Reservoir (O16), nesting began in 2000 with a single pair with nestlings 21 June (D. C. Seals). The next year, on 9 July, one eucalyptus tree overlooking the lake contained three nests of the Great Egret, two of the Snowy, and one of the Great Blue Heron (J. R. Barth, R. T. Patton, P. Unitt). At Lindo Lake, Lakeside (P14), Great Egret nesting also began in 2000, with one carrying nest material 18 May (M. B. Stowe). On 9 July 2001, there were five nests of the Great Egret, among more of the Great Blue Heron, Snowy Egret, and Black-crowned Night-Heron (J. R. Barth, R. T. Patton, P. Unitt). On 11 August 2001, on the south side of the San Dieguito River estuary (M7), one nest of the Great Egret, near two of the Great Blue Heron, had two nearly full-grown nestlings (P.Unitt). In the Great Blue Heron colony at the Point Loma navy research laboratory (S7), one pair of the Great Egret nested in 2000 but failed. In 2002, however, two pairs nested at this site, one successfully, and in 2003 three pairs nested, all successfully (M. F. Platter-Rieger).

Yet another new colony formed in 2000 was at the east end of Lake Wohlford (H12), with six birds on 28 May (P. Hernandez, S. Christiansen, E. C. Hall). On 20 May 2001, the colony appeared to be growing rapidly, with 35 individuals in courtship displays and nest building and incubation apparently begun in one nest. Less than seven weeks later, however, on 7 July, the colony had been deserted and not a single egret remained in the area (P. Unitt).

The establishment of new colonies continued after the atlas period with three nests of the Great Egret on the north side of Batiquitos Lagoon (J7) in 2003 (R. Ebersol).

Away from breeding colonies, the Great Egret is widespread at both coastal and inland wetlands. Some of the larger concentrations, up to 75 at Lake Hodges 14 June 1999 (R. L. Barber) and 61 at San Elijo Lagoon 10 July 1999 (P. A. Ginsburg), were probably of birds commuting from or recently fledged from nearby colonies. But others, such as 16 at O’Neill Lake (E6) 9 June 1998 (P. A. Ginsburg), 33 at Batiquitos Lagoon 3 April 1998 (F. Hall, C. C. Gorman), and 18 at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7) 3 April 1999 (K. Estey) were not—though they suggest sites for future colonies. In the mountains the Great Egret is rare during the breeding season, with reports of no more than two (at Wynola, J19, 17 April–2 July 1999, S. E. Smith; near Julian, K20, 10 June 1998, E. C. Hall).

Nesting: Like the Great Blue Heron, the Great Egret builds a platform of sticks high in trees. In the mixed colony at Rancho Santa Fe, the Great Blue’s nests were higher, above the egrets’. At most sites in San Diego County, the nests are in eucalyptus, but at the San Dieguito River mouth and Point Loma the birds were in Torrey pines; at Lake Wohlford they were in coast live oaks.

The schedule of Great Egret nesting in San Diego County is variable. In 1998, egg laying in the Rancho Santa Fe colony had apparently begun by late February; a search underneath the colony on 5 March yielded some broken eggs fallen to the ground (A. Mauro). By 11 May some young from this colony had already fledged while others were still downy. At Point Loma the young hatched in May and June (M. F. Platter-Rieger). The large nestlings at the San Dieguito River mouth 11 August 2001 must have hatched from eggs laid in early June.

Migration: Although the Great Egret has colonized San Diego County as a nesting species, its primary role is still that of a nonbreeding visitor. Censuses around San Diego Bay show the egret’s numbers peaking from November to February and reaching their nadir in June, with gradual changes between. Around north San Diego Bay, Mock et al. (1994) had their high count of 88 on 9 November 1994; in the salt works, Stadtlander and Konecny (1994) had their high count of 83 on 17 November 1993. Postbreeding dispersal to higher elevations is underway by August, with up to ten at Cuyamaca Lake (M20) 10 August 1998 (J. R. Barth).

In and near the Anza–Borrego Desert, the Great Egret occurs primarily as a rare migrant, recorded in fall as early as 21 July (1994, three at the Roadrunner Club, Borrego Springs, F24, M. L. Gabel), in spring as late as 6 May (1999, one at Banner, K21, P. K. Nelson). Generally the species is seen singly; exceptional concentrations are of ten at the Borrego Springs sewage pond (H25) 10 October 1992 (A. G. Morley) and seven in the north Borrego Valley (E24) 6 May 2000 (P. D. Ache). Most desert records are from the Borrego Valley, but a few are from scattered localities far from suitable habitat, such as Ocotillo Wells (I28; two on 1 April 2000, R. Miller) and Canyon sin Nombre (P29; one on 29 April 2000, F. A. Belinsky, M. G. Mathos).

Winter: In the coastal lowland, wintering Great Egrets are widespread and locally common. Many of the birds in the Wild Animal Park remain through the winter, with up to 71 on 30 December 2000 (K. L. Weaver). Farther inland, the egret is uncommon and scattered, with up to five in Ramona (K15) 30 December 2000 (D. and C. Batzler) and seven at Barrett Lake (S19) 5 February 2000 (R. and S. L. Breisch). Even as high as Cuyamaca Lake the Great Egret is fairly regular in winter, with up to two on 18 February 1999 (A. P. and T. E. Keenan).

In the Anza–Borrego Desert in winter the Great Egret is rare, with just four records of single birds from 1997 to 2002. It has been recorded on just three of 18 Anza–Borrego Christmas bird counts 1984–2001, though the count on 20 December 1987 yielded eight.

Conservation: The Great Egret was decimated in southern California around 1900, when the birds were killed for their plumes, in fashion for decorating ladies’ hats. Once this trade was suppressed, recovery began. In the winter of 1912–13, Grey (1913b) reported up to 20 at the south end of San Diego Bay 25 December; previously, he had seen no more than four. By 1936, a large roost had formed at Point Loma, with a maximum of “well over 150” on 25 February (Sefton 1936). The population began another upsurge in the late 1970s. King et al. (1987) noted an increase at San Elijo Lagoon from 1973 to 1983. From 1960 to 1977 the San Diego Christmas bird count averaged 26.5 Great Egrets; from 1997 to 2001 it averaged 106.4.

Nesting began in 1988 with a pair at the Dairy Mart pond in the Tijuana River valley (V11; G. McCaskie, AB 42:1339, 1988). This site soon became unsuitable, but the first nesting at the Wild Animal Park took place the following year (J. Oldenettel, AB 43:1367, 1989), and by 1991 the colony had grown to 30 pairs (J. O'Brien, AB 45:1160, 1991).

Herons and humanity have an uneasy relationship. People now admire the Great Egret’s beauty without having to wear it themselves. But heron colonies are messy affairs, unwelcome when they form over public parks like Lindo Lake. The egrets prefer to nest near water where they can feed, so they are likely to choose sites frequented by people where they are hard to ignore and vulnerable to disturbance.

Taxonomy: Great Egrets in the New World are A. a. egretta Gmelin, 1789, differing from the subspecies in the Old World by their almost wholly yellow bills.

Snowy

Egret

Egretta thula

Snowy

Egret

Egretta thula

One of California’s most elegant birds, the Snowy Egret frequents both coastal and inland wetlands. Since the 1930s, when it recovered from persecution for its plumes, it has been common in fall and winter. Since 1979, it has also established an increasing number of breeding colonies. Yet, in contrast to the Great Egret, the increase in Snowy Egret colonies has not been accompanied by a clear increase in the Snowy’s numbers. Though dependent on wetlands for foraging, the Snowy Egret takes advantage of humanity, from nesting in landscaping to following on the heels clam diggers at the San Diego River mouth, snapping up any organisms they suck out of the mud.

Breeding distribution: The first recorded Snowy Egret colonies in San Diego County were established at Buena Vista Lagoon in 1979 (J. P. Rieger, AB 33:896, 1979) and in the Tijuana River valley in 1980 (AB 34:929, 1980). By 1997 these were no longer active, but during the atlas period we confirmed nesting at eight other sites. Because Snowy Egrets often hide their nests in denser vegetation than the Great Egret and Great Blue Heron, assessing the size of a Snowy Egret colony is more difficult than for the larger herons.

Two of the largest colonies lie near San Diego and Mission bays. The colony on the grounds of Sea World, behind the Forbidden Reef exhibit (R8), was founded in 1991 and contained 42 nests and fledged 44 young in 1997 (Black et al. 1997). The colony within North Island Naval Air Station (S8) contained 37 nests and fledged 15 young in 1999 (McDonald et al. 2000). Another large colony is in the mixed heronry at the Wild Animal Park in the Heart of Africa exhibit (J12). Our maximum count of individuals here was 150 on 15 June 1998 (D. and D. Bylin); there were at least 14 active nests on 9 May 1999 (K. L. Weaver). The colony in Solana Beach (M7) at the corner of Plaza Street and Sierra Avenue had 10–20 nests in 1997 and was still active in 2001 (A. Mauro).

Other colonies are small or new. In the San Luis Rey River valley just east of Interstate 15, at least one pair nested in 2000 and 2001 at a pond formed when a new housing development blocked the drainage of Keys Canyon (E9; C. and D. Wysong, J. Pike). At Guajome Lake (G7), at least eight pairs nested in 2001 (K. L. Weaver). At El Capitan Reservoir (O16) Snowy Egrets founded a new colony in 2001, two pairs nesting in one eucalyptus tree with three pairs of the Great Egret and one of the Great Blue Heron (J. R. Barth). Snowy Egrets helped found the mixed heronry at Lindo Lake (P14) in 2000 (M. B. Stowe); they had about five active nests there on 9 July 2001 (P. Unitt). In 2002 Snowy Egrets joined the Great Blue Herons on the north side of Batiquitos Lagoon (J7); in 2003 there were about five nests of the Snowy (R. Ebersol). At the mouth of the San Luis Rey River—in trees over the parking lot of a Jolly Roger restaurant (H5)—were 48 nests of the Snowy Egret, plus four of the Great Blue Heron and two of the Black-crowned Night-Heron, on 3 July 2003 (K. L. Weaver). Information from nonbirders in the area, including one of the restaurant’s managers, suggests that this colony, although probably not new, increased greatly in 2002 and 2003 (J. Determan).

Even during the breeding season Snowy Egrets are widespread in the coastal lowland away from nesting colonies. Some high counts exemplifying this are of 60 at Lake Hodges (K10) 16 June 1999 (R. L. Barber), 29 at Batiquitos Lagoon 1 May 1998 (F. Hall), and 25 at the upper end of Sweetwater Reservoir (S13) 23 March 2001 (P. Famolaro). In the foothills the Snowy Egret is uncommon and scattered in the breeding season, with counts of up to five only, as at Sutherland Lake (J16) 25 June 2000 (J. R. Barth). In the mountains the Snowy Egret is rare, reported during the atlas period only from Wynola (J19; up to two on 17 April 1999, S. E. Smith) and Cuyamaca Lake (M20; one on 25 June 1998, A. P. and T. E. Keenan).

Nesting: Even though San Diego County colonies are few, they encompass a surprising variety of nest sites. At Solana Beach, where the egrets nest in company with Black-crowned Night-Herons only, the nests are in a dense-foliaged fig tree. At North Island, also shared with the night-heron, the nests are in eucalyptus and pines as well as figs. The mixed heronries at Lindo Lake and El Capitan Reservoir are in eucalyptus trees. At Sea World, where the only species nesting in close association with the Snowy Egret is the Little Blue Heron, most of the nests are in thick bamboo, a few in figs. At Guajome Lake and Keys Canyon, where the egrets’ companions are White-faced Ibises, the birds nest on islands of matted cattails.

The schedule of Snowy Egret nesting in San Diego has been monitored most closely at Sea World (Black et al. 1997). In 1997, incubation had apparently begun in some nests by 21 March, and most young fledged between 22 May and 21 June, corresponding to laying from late March to late April. But eight nests were still active on 20 August, suggesting egg laying as late as the end of June.

Migration: Although the Snowy Egret occurs in San Diego County year round, its numbers vary with the seasons. Surveys of San Elijo Lagoon (King et al. 1987) and north San Diego Bay (Mock et al. 1994) found it most numerous in fall; those of south San Diego Bay (Macdonald et al. 1990, Stadtlander and Konecny 1994) found it most numerous in winter. Generally it is least numerous in summer.

In the Anza–Borrego Desert the Snowy Egret is a rare migrant, recorded mainly at artificial ponds, only a few times at natural oases, from 22 September (1999, four at the Borrego Springs sewage pond, H25, A. G. Morley) to 27 May (1990, one along Vallecito Creek, M24, Massey and Evans 1994). The only desert records of more than five individuals were of 11 in Borrego Springs (G24) 3 April 1999 and 19 there, in a pond filled by a flash flood, 24 August 2003 (P. D. Ache).

Winter: In winter, the Snowy Egret is more widespread than in spring or summer, visiting small ponds as well as larger lakes throughout the coastal lowland. The Wild Animal Park remains a major center for the species, with winter counts as high as 100 on 30 December 1999 (D. and D. Bylin). Along the coast, notable late fall or winter concentrations have been of up to 152 around north San Diego Bay 11 November 1994 (Mock et al. 1994), 91 at the outflow channel for the power plant in Chula Vista 7 February 1989 (Macdonald et al. 1990), and 115 in the salt works 17 November 1993 (Stadtlander and Konecny 1994).

Even in the foothills and mountains the Snowy Egret is more of a winter visitor. Our winter counts in this region ranged up to eight, at Barrett Lake 2 February 2001 (R. and S. L. Breisch) and at Corte Madera Lake (R20) 20 February 1999 (L. and M. Polinsky). Winter records range as high as 4000–4200 feet elevation near Julian (J20, one on 2 December 1999, M. B. Stowe; K20, one on 1 December 1997, E. C. Hall). There are only five winter records from the Anza–Borrego Desert, two during the atlas period, of one in Borrego Springs (G24) 9 February 1998 (P. D. Ache) and one at Tamarisk Grove (I24) 31 January 1999 (R. Thériault).

Conservation: Though “plentiful at all seasons” along the coast of southern California in the 1860s (Cooper 1870), the Snowy Egret was the species most gravely affected by hunting for hat plumes. It went unrecorded in San Diego County from 1890 to 1922. Recovery took place largely from 1929 to 1939. The egret’s colonization of San Diego County beginning in 1979 suggests that another population expansion is underway, in parallel with the Great Egret’s. Yet Christmas bird counts suggest another story, that the number of Snowy Egrets, at least in winter, peaked in the 1970s and 1980s and may have declined since the early 1990s. The factors governing Snowy Egret numbers in San Diego County, and the degree to which the birds move in and out of the county, are unknown.

Taxonomy: Snowy Egrets in San Diego County, like those elsewhere in the western United States, are closer in size to those of the eastern half of the country, smaller and thinner billed than those of Baja California, and so best called E. t. candidissima (Gmelin, 1789) (Rea 1983).

Little

Blue Heron

Egretta caerulea

Little

Blue Heron

Egretta caerulea

The Little Blue Heron is a rather recent arrival in San Diego County, since the 1980s a rare but permanent resident of the coastal wetlands. It forages in shallow water and nests in colonies of its close relative, the Snowy Egret. Indeed, the egret’s colonizing the county may have been a necessary precursor to the Little Blue Heron’s colonizing. San Diego now represents the northwestern corner of the Little Blue Heron’s usual range.

Breeding distribution: From 1997 to 2001 the Little Blue Heron was confirmed nesting only in the Snowy Egret colony at Sea World (R8), where one pair fledged one young in 1997 (Black et al. 1997). In 1993 and 1994, however, three and four pairs of the Little Blue nested there, respectively. Also, at least one pair evidently nested in the heronry within North Island Naval Air Station (S8) in 1996, as a recently fledged juvenile was picked up moribund beneath the colony 20 August (SDNHM 49605). Surveys there in 1999 did not reveal the species (McDonald et al. 2000)

Foraging Little Blue Herons are seen along the shores of Mission Bay, in the San Diego River flood-control channel (up to five on 29 July 2000, M. Billings), at Famosa Slough, in south San Diego Bay, and in the Tijuana River estuary. They have been seen repeatedly at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7) but are rare farther north. The species has been recorded at most of the coastal lagoons between Del Mar and Oceanside, but during the atlas period the only summer records north of Los Peñasquitos Lagoon were of one at the Santa Margarita River mouth (G4) 15 June 1997 (B. Peterson) and 3–5 July 1999 (P. A. Ginsburg).

Nesting: The Snowy Egret/Little Blue Heron colony at Sea World is in a thick stand of tall bamboo (Black et al. 1997). The mixed heronry at North Island is spread among eucalyptus, pine, and fig trees. Information on the species’ nesting schedule in San Diego County is still rudimentary. In 1994, one nest at Sea World was occupied by 8 April; in 1997, the nest was occupied by 6 May and the young fledged between 21 June and 12 July. In the former colony in the Tijuana River valley, fledging was in July.

Winter: The Little Blue Heron’s distribution and abundance in San Diego County in winter are much the same as at other seasons. An exceptional winter concentration, the largest yet reported, was of 14 in the San Diego River flood-control channel 23 December 1997 (C. G. Edwards). Winter records from northern San Diego County were of two at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon 5 December 1999 (D. K. Adams), one at the San Dieguito River estuary 11 December 1999 (D. R. Grine), and one immature 5.8 miles inland at a sewage pond in the Santa Margarita River valley, Camp Pendleton (E5), 25 December 1999 (B. E. Bell).

Conservation: The Little Blue Heron was first recorded in San Diego County on 14 November 1967 (AFN 22:89, 1968) and remained a rare visitor until 1980. From then through 1993, one or two pairs nested in the multispecies heronry at the Dairy Mart pond, Tijuana River valley (V11). That colony disappeared, but the herons began nesting at Sea World in 1992. Since the mid 1980s the population of Little Blue Herons in the San Diego area seems to have been more or less stable at approximately 10–12 individuals. The close association in nesting between the Little Blue Heron and Snowy Egret suggests that the career of the former will follow in the steps of the latter.

Tricolored Heron Egretta tricolor

Like the Reddish Egret, the Tricolored or Louisiana Heron is a rare visitor from the south that reaches the northern tip of its normal range at San Diego. The Tricolored is most often seen foraging like other herons in the channels through the Tijuana River estuary or in shallow water around south San Diego Bay. Unlike many other herons, which are on the increase, the Tricolored has been decreasing in frequency since the mid 1980s, though one shows up in most winters.

Winter: The Tijuana River estuary (V10/W10) was our only site for more than a single Tricolored Heron 1997–2002, with two (one adult, one immature) there 5 December 1999 (B. C. Moore). There were also repeated observations around south San Diego Bay (T9/U10), with birds presumably moving between there and the Tijuana estuary. During the atlas period, a Tricolored Heron also showed up twice in the San Diego River flood-control channel (R8; 9 June–3 July 1999; 6 November–9 December 1999, T. Hartnett, J. R. Sams, NAB 54:104, 220, 2000), once at Kendall–Frost Marsh, Mission Bay (Q8; 29 December 1998, J. C. Worley).

Migration: The Tricolored Heron has been seen in San Diego County in every month of the year, but is least frequent in summer. Immatures may arrive in fall as early as 23 September (1978, AB 33:213, 1979). Usually the birds disappear by 1 May, but some have remained through the summer, as in 1984 (AB 38:958, 1061, 1984). About a dozen have apparently arrived in summer.

Though largely coastal, Tricolored Herons have been found three times at fresh water in the Tijuana River valley (Unitt 1984) and once at Lake Henshaw (G17; 18 October 1983, R. Higson, AB 38:246, 1984). Because the species is also a rare visitor to the Salton Sea, this bird may have moved into San Diego County from the east.

Conservation: Laurence M. Huey (1915) found the Tricolored Heron in San Diego County (and California) for the first time at the south end of San Diego Bay 17 January 1914 (SDNHM 30889). For the next 40 years, while observers were few, the species was seen irregularly. But from the mid 1950s through the mid 1980s, with an increase of birders, the heron proved regular along San Diego’s coast in small numbers. During this interval, it occurred occasionally in the lagoons of northern San Diego County, with up to six at San Elijo Lagoon (L7) 1 November–27 December 1963 (McCaskie 1964). Since 1980, however, the only Tricolored Herons in coastal north county have been one at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7) 8 January 1984 (D. B. King, AB 38:357, 1984) and one there 1 May 1988 (B. C. Moore, AB 42:481, 1988). In the San Diego area the numbers peaked in 1979–80 with five (AB 34:306, 1980). The winter of 1984–85 was the last with as many as three (AB 39:209, 1985). Nevertheless, at least one showed up each subsequent year through 2001 except the winter 1996–97.

Dredging and filling of the bays, siltation of the lagoons, and development of the shoreline have eliminated much Tricolored Heron habitat. The species was regular at Mission Bay before that area was developed (Sams and Stott 1959). Nevertheless, the increase of some other herons suggests that other factors are likely contributing to the Tricolored Heron’s decrease, perhaps a diminution of the source population in Baja California.

Taxonomy: Tricolored Herons throughout North America are E. t. ruficollis Gosse, 1847, as E. t. occidentalis (Huey, 1927), described from Baja California, is generally considered a synonym.

Reddish

Egret

Egretta rufescens

Reddish

Egret

Egretta rufescens

San Diego County marks the northern limit of the Reddish Egret’s usual range along the Pacific coast. Though the species does not (yet) nest here, two or three occur in the county’s coastal wetlands each year as nonbreeding visitors. Though rare, the Reddish Egret calls attention to itself by its animated behavior, dashing about erratically in shallow water with wings spread, ready to nab any small fish its gyrations may startle.

Winter: The Reddish Egret has been seen in most of San Diego County’s coastal wetlands but is considerably more frequent in the San Diego area than in the north county lagoons. Over the final quarter of the 20th century an average of between two and three reached San Diego County each year. The exact number is often impossible to determine as the birds move up and down the coast. The Reddish Egret is usually seen singly (though often near other foraging herons); during the atlas period two were noted at the south end of San Diego Bay (V10) 14 May 2000 (Y. Ikegaya; NAB 54:326, 2000) and in the San Diego River flood-control channel (R7/R8) 26 December 2001–7 February 2002 (M. Billings, NAB 56:223, 2002).

Sites along the coast of northern San Diego County where the Reddish Egret have been found are Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7; two from 6 to 12 September 1968, AFN 23:107, 1969; one from 9 to 23 January 2000, D. K. Adams), the San Dieguito River estuary (M7; 8–24 October 1990, G. Deeks, Heindel and Garrett 1995; 16–19 October 1991, J. O’Brien, Patten et al. 1995b; 25 September 1999–30 January 2000, B. Foster, R. T. Patton, NAB 54:104, 220, 2000), San Elijo Lagoon (29 September 1968 and 13 December 1969, King et al. 1987; 19 May 1991, R. T. Patton, Heindel and Garrett 1995; 11–24 September 2000, D. Trissel, McKee and Erickson 2002), Batiquitos Lagoon (11–18 September 1962, King et al. 1987; 6 September–12 December 2001, G. C. Hazard, M. Baumgartel, NAB 56:223, 2002), and the Santa Margarita River estuary (17 April–3 May 1981, L. Salata, Langham 1991; 25 August 2001, B. Foster).

Migration: The Reddish Egret has been seen in San Diego County in every month of the year, but its frequency peaks in October and November with the dispersal of immatures. Yet the largest number recorded, seven at the south end of San Diego Bay, was seen on 6 May 1990 (G. McCaskie; Patten and Erickson 1994). The Reddish Egret is least frequent in June and July, with only about five records for each of those months.

Though the Reddish Egret has wandered on several occasions from the Gulf of California to the Salton Sea (Patten et al. 2003), in coastal southern California it sticks to the coastal wetlands almost exclusively. Except for four birds that moved a short distance inland in the Tijuana River valley, the only well-supported inland record for San Diego County is of an immature found in a weakened condition at a backyard goldfish pond along Tobiasson Road in Poway (M11) 6 September 2002 (SDNHM 50658).

Conservation: The numbers of the Reddish Egret reaching San Diego County appear to be on a gradual increase. From the time of the first report in 1931 (Huey 1931b) through the early 1970s the species was casual, but since 1980 not a year has passed without at least one. The increase is paralleled by a northward extension of the species’ breeding range in Baja California. In 1999 two pairs colonized Islas Todos Santos off Ensenada (Palacios and Mellink 2000). Some day the Reddish Egret may join some of the mixed-species heronries around San Diego.

Taxonomy: Reddish Egrets in California have been ascribed to the west Mexican subspecies E. r. dickeyi (van Rossem, 1926), adults of which are said to have a head and neck darker than in the nominate eastern subspecies. Both specimens from San Diego County (the one from Poway and one from the Tijuana River estuary 23 October 1963, SDNHM 30757, McCaskie 1964) are immatures, however, so cannot be identified.

Cattle

Egret

Bubulcus ibis

Cattle

Egret

Bubulcus ibis

The Cattle Egret has enjoyed the most explosive natural range expansion of any bird in recorded history. In 25 years it went from being a new arrival to the most abundant bird in southeastern California’s Imperial Valley. In San Diego County, however, it has seen a reversal as well as an advance. Since the species first nested in 1979, colonies have formed and vanished in quick succession; from 1997 through 2001 the only important one was that at the Wild Animal Park. After a peak in the 1980s the population has been on the decline; the conversion of pastures and dairies to urban sprawl spells no good for this bird whose lifestyle is linked to livestock.

Breeding distribution: The Cattle Egret colony at the Wild Animal Park (J12) is part of the mixed-species heronry in the Heart of Africa exhibit—a site eminently suitable for this species of African origin. Maximum numbers reported here in the breeding season during the atlas period were 100 individuals on 15 June 1998 (D. and D. Bylin) and 43 nests on 9 May 1999 (K. L. Weaver).

In 2001, one or two pairs nested in the multispecies heronry at Lindo Lake, Lakeside (P14). One pair was feeding nestlings on 12 May (C. G. Edwards), but by 9 July no Cattle Egrets were in the colony.

Cattle Egrets from the Wild Animal Park colony evidently forage west to Escondido (J10; over 100 on 14 May 1997, O. Carter) and southeast to the Santa Maria Valley surrounding Ramona (L14; up to 88 on 28 March 1999, F. Sproul; K15, up to 300 on 4 April 1998, P. Unitt). The Ramona region currently offers the most foraging habitat for the Cattle Egret in San Diego County. Cattails in the pond on the north side of Highway 78 just west of Magnolia Avenue (K15) are a frequent Cattle Egret roost.

Beyond a 15-mile radius of the Wild Animal Park, the Cattle Egret is uncommon and irregular, especially during the breeding season. It is still rather frequent in the San Luis Rey River valley between Oceanside and Interstate 15 (up to 18 in northeast Oceanside, F7, 26 April 1997, A. Peterson). In southern San Diego County the largest flocks during the breeding season from 1997 to 2001 were of 12 at the upper end of El Capitan Reservoir (N17) 9 July 1999 (D. C. Seals) and 25 on Otay Mesa (V13) 10 May 1998 (P. Unitt). In the eastern half of the county the Cattle Egret is rare at this season; the only sighting of more than two birds was of 10 at Crestwood Ranch (R24) 20 May 2000 (J. S. Larson).

Nesting: The Cattle Egret builds a rough stick nest similar to that of other herons. Within a colony the nests may be packed so closely the incubating birds are within pecking distance of each other. The schedule of Cattle Egret nesting in San Diego County is not well defined and probably variable, at least when new colonies are forming. At the Animal Park the birds have been seen apparently incubating by 18 April and to have young in the nest at least as late as 15 June (D. and D. Bylin). In the enormous heronries of the Imperial Valley, some young are still in nests as late as early September.

Migration: The Cattle Egret follows no well-defined migration in southern California, though it obviously disperses long distances. A bird color-marked at a nesting colony near the Salton Sea was seen near the Otay dump 15 November 1975 (AB 30:125, 1976).

Winter: In winter the Cattle Egret remains concentrated at the Wild Animal Park (up to 389 on 30 December 2000, K. L. Weaver), elsewhere in the San Pasqual Valley (up to 400 near Fenton Ranch, K13, 3 January 1998, M. Forman), and near Ramona (K15; up to 350 on 31 December 1998, M. and B. McIntosh), Escondido, San Marcos, and Valley Center—places all still within 15 miles of the Wild Animal Park. A secondary area of winter concentration during the atlas period was along the Sweetwater River from Sweetwater Reservoir (S12) to the Singing Hills golf course, especially in the Jamacha area (R13; up to 200 on 2 January 2000 (M. and D. Hastings).

Numbers in northwestern San Diego County are somewhat higher in winter than during the breeding season, with up to 40 on lawns near O’Neill Lake (E6) 10 January 2001 (P. A. Ginsburg) and 40 at Bonsall (F8) 27 February 2001 (M. Freda). Cattle Egrets show up occasionally in coastal wetlands in winter, with up to 10 north of Batiquitos Lagoon (J6) 30 December 1997 (M. Baumgartel) and six at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7) 3 January 1998 (K. Estey).

In eastern San Diego County the Cattle Egret is as rare in winter as in the breeding season, and again Crestwood Ranch was the only site of more than three, with 10 on 7 February 2000 (J. S. Larson). In the Borrego Valley we made only three sightings of one or two Cattle Egrets during the atlas period, all seasons combined, but earlier records there ran as high as 18 on 12 December 1990 (A. G. Morley).

Conservation: The first Cattle Egrets found in San Diego County, among the earliest for California, were in the Tijuana River valley 7 March 1964 (McCaskie 1965, SDNHM 35075). The species increased gradually as a nonbreeding visitor until fall 1977, when there was a large influx. Nesting began at Buena Vista Lagoon in 1979 (AB 33:896, 1979), at the Dairy Mart Pond in the Tijuana River valley in 1980 (AB 34:929, 1980), and at Guajome Lake in 1983 (AB 37:1026, 1983). All these colonies proved ephemeral, however, and the population peaked in the 1980s, then declined as abruptly as it increased. Totals on San Diego Christmas bird counts, mainly from the Tijuana River valley, increased from an average of 5.3 from 1966 to 1976 to a peak of 3512 in 1985, then decreased to six in 1995. Since then that count has had none. During the five-year atlas period we had not a single Cattle Egret in the Tijuana River valley—where 15 years earlier there were thousands. On the Oceanside count the total peaked at 1087 in 1979, and a decrease was noticeable even from 1997 to 2001. Even on the Escondido count, whose circle encompasses most of the county’s current Cattle Egret habitat, the number peaked at 875 in January 1997; during the atlas period a decline was almost continuous.

Why should the Cattle Egret have failed to maintain its abundance in San Diego County, as it has just to the east in the Imperial Valley? The most obvious contributing factor is the relative dearth of foraging habitat—and the decline in this habitat as agriculture gives way to urban development. The explosive increase of the late 1970s was due to immigration, and the sources of these immigrants may have stabilized.

Taxonomy: The nominate subspecies of the Cattle Egret, B. i. ibis (Linnaeus, 1758), crossing the Atlantic Ocean from Africa, is the one that colonized the New World, beginning on the Atlantic coast of South America.

Green

Heron

Butorides virescens

Green

Heron

Butorides virescens

Unlike most herons, which forage in the open in marshes and along shorelines, the Green Heron prefers to fish in ponds and channels bordered or shaded by trees. It is thus as much a bird of riparian woodland as one of marshes. And unlike many other herons it is not colonial, at least in San Diego County, so it appears uncommon. But because it takes advantage of many small wetlands little used by the other species its population in the county may be just as large.

Breeding distribution: In San Diego County the Green Heron is most widespread in the northern part of the coastal lowland, where strips of riparian woodland and small ponds are most frequent. In the southern part of the county the distribution clearly traces the major rivers and lakes. Thirty at Lake Hodges (K10) 14 June 1999 (R. L. Barber) and 16 at Lower Otay Lake (U14) 4 July 1999 (S. Buchanan) were exceptionally high counts; otherwise, we noted no more than eight per day per atlas square. Small numbers use the scattered wet areas of southeastern San Diego County (family with three fledglings 19 June 1999 at Twin Lakes or Picnic Lake near Potrero, U20, R. and S. L. Breisch) and in the Julian area (up to two at Wynola, J19, 12 March 1999, S. E. Smith). The highest elevation at which we found the Green Heron during the atlas period was 4600 feet in Lost Valley (D20; one on 2 June and 1 July 1999, J. M. and B. Hargrove, W. E. Haas).

Draining the east slope of the mountains, Coyote, San Felipe, and Banner creeks also likely support nesting Green Herons, at least occasionally. Though no nests have yet been found in the Anza–Borrego Desert, the birds are regular along Coyote Creek at Lower Willows (D23) in spring, with a maximum count of five on 25 April 1998 (B. Peterson) and sightings as late as 4 July (1999, B. Getty, K. Wilson).

Nesting: Egg collectors who described the sites of Green Heron nests in San Diego County all reported them in willows. A nest at Barrett Lake (S19) 18 June 2000 (R. and S. L. Breisch) was also in a willow. But the Green Heron may nest in cattails as well: one carrying a twig near Potrero 26 June 1999 took it into a stand of cattails (R. and S. L. Breisch).

The Green Heron has a long breeding season and may raise two broods per year. A fledgling near Valley Center (F12) 18 April 2001 (E. C. Hall) suggests laying as early as the second week of March; a nest at the upper end of Sweetwater Reservoir (S13) still had eggs on 14 July 1998 (P. Famolaro).

Migration: The Green Heron is somewhat less numerous in winter than in summer but does not follow a well-marked schedule of migration. In the Anza–Borrego Desert, away from possible breeding sites, it is reported most frequently in April and May, but these are also peak months for birders in the area. Most desert records are from oases or artificial ponds, but a few are far from water, such as one in a rocky cove on the east side of Blair Dry Lake (L24) 11 April 1999 (R. Thériault).

Winter: The Green Heron’s winter distribution in San Diego County is similar to its breeding distribution but somewhat more patchy. The only site where we noted more than four individuals per day at this season was at and near Whelan Lake, with up to ten on 14 December 2000 (P. A. Ginsburg). In the foothills and mountains wintering Green Herons are scarce, with seldom more than a single bird seen at a time and a maximum of three at Cuyamaca Lake (M20) 4 December 1998 (A. P. and T. E. Keenan). Our only winter records in the desert during the atlas period were of single birds in Borrego Springs (F24) 12 January 1998 and 19 December 1999 (M. L. Gabel, P. K. Nelson). The Green Heron has been noted on four of 18 Anza–Borrego Christmas bird counts 1984–2001, with no more than three birds per count.

Conservation: Early in the 20th century, the Green Heron occurred in San Diego County as a migrant and summer resident only. It was first noted in winter at Lindo Lake (P14) on 1 January 1928 (Huey 1928b) and was as numerous in winter as today by the 1950s. Both the breeding and winter ranges have long been spreading north along the Pacific coast (Davis and Kushlan 1994).

It is unclear how much the Green Heron has suffered from the loss of riparian woodland and freshwater marshes versus how much it has benefited from the importation of water. Results of Christmas bird counts suggest that since 1985 its numbers may be declining gradually.

Taxonomy: Green Herons in California are B. v. anthonyi (Mearns, 1895), whose adults have the neck rufous, not deep maroon as in B. v. frazari (Brewster, 1888) of southern Baja California.

Black-crowned

Night-Heron

Nycticorax nycticorax

Black-crowned

Night-Heron

Nycticorax nycticorax

The Black-crowned Night-Heron spends much of the day resting quietly in marshes or trees, then at dusk flies off to forage, broadcasting a startlingly loud “quock!” In San Diego County it is locally common year round, both along the coast and at lakes and marshes inland. From 1997 to 2001 there were seven substantial colonies in the county, most mixed with other species of herons. Isolated pairs or small colonies also contribute to the population, to an unknown degree.

Breeding distribution: Like the Great Blue, the Black-crowned Night-Heron nests mainly in colonies, often in mixed heronies. Seven sites appear to account for most of San Diego County’s population. At the Wild Animal Park (J12), in the multispecies heronry in the Heart of Africa exhibit, counts of the birds (fledglings included) ranged up to 150 on 15 June 1998 (D. and D. Bylin); our best count of nests was at least 20 on 8 May 1999 (K. L. Weaver). At Sierra Avenue and Plaza Street in Solana Beach (M7), Black-crowned Night-Herons nest in company with Snowy Egrets. There were 10 to 20 nests of the former in a fig tree in 1997, and by 2001 they had spread to some nearby eucalyptus trees (A. Mauro). Pine trees at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (O7) were a colony site for many years, at least until some heavy construction at the campus in 2002. At least three, possibly seven, nests were active on 4 June 1998 (S. E. Smith). In 1999, Black-crowned Night-Herons founded the mixed heronry at Lindo Lake (P14; M. B. Stowe). By 9 July 2001, there were at least 10 nests of the night-heron, among lesser numbers of the Great Blue Heron, Snowy Egret, and Great Egret. The Point Loma submarine base (S7) hosts the county’s longest-known Black-crowned Night-Heron colony, known since the 1970s and reaching a peak size of about 500 nests in 1980. Fledglings at this site suffered high mortality from steatitis, and the colony declined to 103 nests in 1995, 21 in 1996. From 1999 to 2001 the colony consisted of only 15 nests, all in fig trees (M. F. Platter-Rieger). The largest colony during the atlas period was that at North Island Naval Air Station (S8), shared with Snowy Egrets. In 1999, when McDonald et al. (2000) surveyed the colony regularly, the number of adults peaked at 140 and the number of nests peaked at 115 on 21 May. That year, 164 nests fledged a total of 166 young. A third colony near San Diego Bay is that at the 32nd Street Naval Station (T10); it contained about 30 nests in 1997 (M. F. Platter-Rieger).

Kenneth L. Weaver found an apparently isolated pair nesting in a willow along the Santa Margarita River near Fallbrook (C8) 1 May 1999, another in a cottonwood along Temecula Creek near Oak Grove (C16) 16 June 2001. On several other occasions we recorded single adults carrying prey or single families of fledglings begging from their parents, far from known colonies. These sites are scattered through the coastal lowland, inland to Swan Lake (F18) near Warner Springs (13, including a fledgling, 24 June 2000, C. G. Edwards) and Wynola (J19; fledgling on 19 June and 2 July 1999, S. E. Smith). The literature on the Black-crowned Night-Heron speaks only of colonies, yet these observations suggest that in San Diego County isolated pairs are not rare.

Apparently nonbreeding birds are widespread through the spring and summer all along the coast and at many lakes and ponds inland, as high as Cuyamaca Lake (one on 21 May and 5 June 1998 and 5 June 1999, A. P. and T. E. Keenan). Concentrations during the breeding season away from colonies range up to 20 at the east end of Lake Hodges (K11) 18 May 1997 (E. C. Hall) and 30 at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7) 1 April 2000 (K. Estey), but these could be of birds commuting 5 miles or less from nests.

Nesting: Black-crowned Night-Herons build a stick platform in trees, similar to those of other herons of similar size. At some colonies the nests are in open-foliaged eucalyptus or palm trees, but more often the birds select sites that offer more concealment, especially dense-foliaged fig trees, used at Solana Beach, Point Loma, North Island, and 32nd Street.

In San Diego County the Black-crowned Night-Heron begins nesting in February. Our earliest date for birds apparently incubating was 26 February; young already out of the nest at Solana Beach 12 April 1997 (L. Ellis) suggest laying in the third week of February. Early March to early May appears to be the main period of nest initiation.

Migration: On the coastal slope of San Diego County numbers of Black-crowned Night-Herons show no consistent pattern of variation through the year. In the Anza–Borrego Desert the Black-crowned Night-Heron is a rare visitor, recorded in ones or twos, mainly in spring and summer. During the atlas period it was noted seven times in this area, from 30 March (1999, one at Desert Ironwoods motel, I28, L. J. Hargrove) to 20 October (1999, one at Ocotillo Wells, I29, P. D. Jorgensen).

Winter: The Black-crowned Night-Heron’s status in San Diego County in winter is similar to that in the breeding season: locally common and widespread in the coastal lowland, scarce and scattered farther inland. The largest winter concentrations have been reported from Whelan Lake (G6; up to 40 on 26 December 1998, D. K. Adams), the Wild Animal Park (up to 54 on 2 January 1999, K. L. Weaver), and the Dairy Mart pond, Tijuana River valley (V11; up to 40 on 18 December 1999, G. McCaskie). Though we found the night-heron wintering at few sites above 2000 elevation, it is regular in winter at Cuyamaca Lake, with up to 13 on 14 December 1999 (A. P. and T. E. Keenan), and there is a winter sighting at Doane Pond, Palomar Mountain (E14; one on 27 January 1995, M. B. Stowe).

The only winter records for the Anza–Borrego Desert are of one near the Borrego Springs airport (F25) 21 December 1983, two at Santa Catarina Spring (D23) 24 December 1988 (ABDSP database), and one on the Anza–Borrego Christmas bird count 19 December 1993.

Conservation: There is little evidence for changes in the Black-crowned Night-Heron’s abundance in San Diego County, though the results of the Rancho Santa Fe Christmas bird count show a downward trend. The decline of the Point Loma colony has been compensated for by the increase of the North Island colony, at least in part. All the major colonies are in planted trees in areas heavily used by people. Although the night-herons are surprisingly indifferent to people, especially while they are foraging at night, the converse is not always true. In 1992, a homeowner in Solana Beach, annoyed with a Black-crowned Night-Heron colony on his property, hired a tree-trimmer to chop down the tree where the birds were nesting—although he had already contacted the California Department of Fish and Game and had been instructed to remove the tree only after the herons were finished nesting. A neighbor filmed the nests, eggs, and chicks crashing to the ground, and the four surviving chicks were rescued from a dumpster the next morning—two were rehabilitated successfully. The film (broadcast on television) and testimony of neighbors supported a lawsuit by the California Department of Fish and Game, and the homeowner and tree-trimmer ultimately paid a fine.

Taxonomy: The North American subspecies of the Black-crowned Night-Heron is N. n. hoactli (Gmelin, 1789), with whiter underparts than that of South America and less white over the eye than in that of the Old World.

Yellow-crowned

Night-Heron

Nyctanassa violacea

Yellow-crowned

Night-Heron

Nyctanassa violacea

Of the herons that reach San Diego County by dispersing north from Mexico, the Yellow-crowned Night-Heron is by far the scarcest. As few as nine individuals have been recorded, though the species has been seen many times more than this low number implies. One bird associated with the Black-crowned Night-Heron colony at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography for 20 years and probably accounted for all sightings in the county during the atlas period.

Breeding distribution: Even though only one Yellow-crowned Night-Heron joined the colony of the Black-crowned at Scripps (O7), it may have attempted nesting at least in 1989. That year, it "built a nest and stood by its mate sitting on the nest, but the eggs evidently did not hatch" (J. O'Brien, AB 43:1367, 1989). It was seen first at San Elijo Lagoon 25 October 1981 and intermittently into 1983 (T. Meyer; Binford 1985); it was presumed to be the same individual that appeared at Scripps annually from 1983 to 2001. Construction on the campus then disrupted the colony, but it may have relocated nearby, to the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club (P7), where the Yellow-crowned appeared 6 December 2001 (C. Nyhan, NAB 56:223, 2002). The same bird was probably responsible for sightings at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon (N7) 20 November 1999 (K. Messer, NAB 54:104, 2000), La Jolla Valley (L10) (T. Johnson; AB 52:531, 1998), along Rose Creek near Mission Bay (Q8) 22 June 1998 (B. O’Leary), and Famosa Slough (R8) 17–19 May 2001 (V. P. Johnson, NAB 55:355, 2001).

Migration: San Diego County’s other records of the Yellow-crowned Night-Heron are scattered through the year. The first two were in fall at the Tijuana River estuary (V10) 3 November 1962 and 22–25 October 1963 (McCaskie 1964). Two in the Tijuana River near Dairy Mart Road (V11) arrived in summer or fall remained through winter: an adult 30 September 1990–7 January 1991, returning 13 October 1991–31 March 1992, joined by a subadult 16 June 1991–13 February 1992 (G. McCaskie; Heindel and Garrett 1995, Patten et al. 1995b). Spring and summer records are of adults at Sea World (R8) 3 April 1979, the Tijuana River estuary 15 April–2 May 1979 (same bird?), the south end of San Diego Bay (V10) 18–26 July 1980 (Binford 1983), and the Santa Margarita River mouth (G4) 9 May 1984 (L. R. Hays, Roberson 1986), and a subadult at San Elijo Lagoon 11 June–24 September 2002 (B. Chaddock, NAB 56:486, 2002, 57:117, 2003).

The California Bird Records Committee questioned the identification of an immature at San Elijo Lagoon 1–11 November 1963 (McCaskie 1964, Roberson 1993).

Taxonomy: The one specimen from San Diego County, from the Tijuana River estuary 25 October 1963 (SDNHM 30758) is the large-billed subspecies N. v. bancrofti Huey, 1927, from the Pacific coast of Mexico, rather than the smaller-billed nominate subspecies from the southeastern United States (McCaskie and Banks 1966, Unitt 1984).